Twenty-five years ago, a genocide was unfolding across Rwanda, bringing the most horrifying violence and bloodshed to towns and villages. In the space of just 100 days from April to June 1994, some 800,000 Rwandans, mostly Tutsis, were to die in the Rwandan genocide. Those who survived would spend years trying to recover from the trauma they experienced.

One of those survivors is Denise Uwimana, who in the midst of an attack on her village, went into labour. She miraculously survived with her newborn and two other sons when Hutu attackers ransacked her home. But others who had been hiding there were killed, including her cousin, who was beheaded in front of her. Tragically, her husband was also killed.

In spite of her horrific experiences, she found a way through the pain with the help of God and now spends her time bringing healing to communities that were affected by the genocide through the organisation she founded, Iriba Shalom International.

She speaks to Christian Today about her journey towards healing here.

CT: It must be hard to put into words what you saw during the terror of the genocide. Did you ever question where God was?

DU: Since my childhood, I loved God because my parents gave us a Christian education, but during the genocide against the Tutsi, I experienced evil things done by Christians that were totally contrary to what my parents and my church had taught us. I lived through a journey of hell on the earth where every day I was a victim to be killed.

But all religions were involved directly or indirectly in killing Tutsi people and I had many questions to God about why He did not intervene to stop the killing.

My firstborn, who was four and a half years old at the time, asked me: "Mama is this the end of the world as people used to say?" I did not have any answer to my child. Then he sang: "God still loves us; He will never put his hands away from us."

I thought about whether there was no longer a God. And if there was still a God, I thought He was only a God for Hutu people and not for Tutsi. I thought that God loved Hutu people more than Tutsi because we were killed and no one dared to say stop.

CT: What role did faith play in your healing?

DU: I was struggling with God during the genocide because of the promises I received from God before it broke out - "I will protect you" and "what a man cannot do for you, I, God will do it for you."

But finally, my relationship with God was deepened by my suffering. The suffering I passed through sustained my relationship with Jesus Christ, because He himself suffered and He was tempted and is able to help those who are being tempted.

Without faith or God's Word, which I obeyed, I would not have been able to take that step towards the perpetrators and forgive them publicly. That played, of course, a great part in my healing.

And healing would also not have been possible without a fellowship with other widows of the genocide. We gathered not only to exchange our experiences – which was important enough - but also to pray and listen to the Word of God for our situation, to encourage each other in faith and love.

CT: How do you cope with traumatic memories? Has anything made your experience easier to deal with?

DU: Survivors of the genocide against the Tutsi always suffer from traumatic memories because we live with the effects of the genocide in our daily life. Still our children ask us why they do not have a father. The orphans who survived and who now have married and got children of their own ask why they cannot visit grandparents, uncles, cousins.

But the way I cope with traumatic memories is to share my suffering, my sorrow - and also my joy - with other survivors in a community or a group of people who understand my sufferings and who are ready to listen to me. It helped me to feel valued as a human being because before, we were regarded as snakes and cockroaches.

And serving others has also played a good role in the process of healing my trauma. I realised that at least I could change the life of my colleagues by showing them love and giving back the dignity which they lost during the genocide.

CT: Do you ever fear it might happen again?

DU: I do not ask myself such a question of whether the genocide might come back again in Rwanda. But I know that if we Rwandans are not awake, divisions might arise again. We are there to say: "Never again" and "We all are Rwandans". And we have a good government which supports unity and reconciliation and is against any new propaganda promoting divisions or revisionism. Trusting in God does not mean to be blind, but God makes us attentive to new dangers, especially against all forms of discrimination, which is always the first step to genocide.

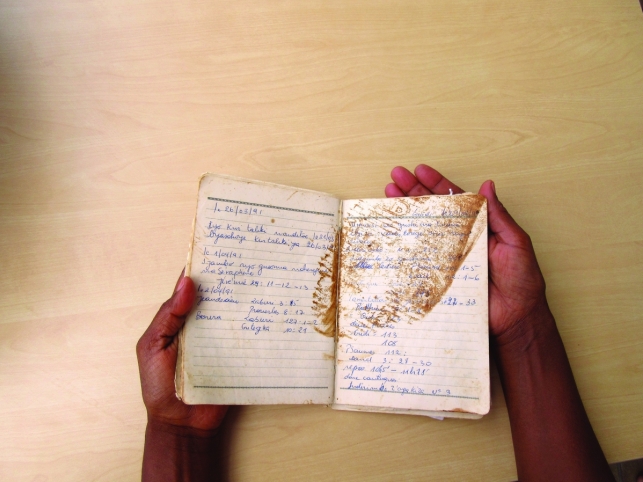

CT: Was writing about your experience of the genocide painful? Did it help in the healing process?

DU: Sure, it is always painful when I speak or write about such horrible experiences of the genocide. But it helped me in the healing process with my wounds. If I kept the horrible things in my soul, they would destroy my whole life and I would become mentally sick.

The better way is to download the heavy burden from the soul, because the soul needs healing. Prayer and the encouragement of friends also helped me to get the strength to speak about such terrible things. When I share my

testimony, my soul gets healed and I heal also the souls of other people who hear about how I overcame the trauma.

Sharing the message in my book has another important meaning. I did not want to lead people into sadness or into depression but I wanted to encourage them to put their trust in Jesus Christ in any situation because He is the one who gives us a true healing. He gives us the strength to forgive in all situations.

CT: What have you learned about forgiveness as a result of what you experienced?

DU: The most important thing is to not be overcome by the evil but overcome the evil with good. Forgiveness makes the impossible to be possible. I was able to forgive and when I did this, it helped me to live again in peace with the perpetrators, some of whom were my neighbours. That is also the same for all who were able to forgive the killers in Rwanda.

Through the power of the resurrection of our Saviour Jesus Christ, we have got the mercy to forgive in all situations.

But in Rwanda we have learned that both are important: personal forgiveness and justice by the state so that the perpetrators are brought to court after three decades of impunity.

Forgiveness does not mean to minimise the guilt, evil is real evil and must not be swept under the carpet. So it is a process. We forgive the enemies but it does not mean that we forget what they did to us. We do remember but without resentment in our heart. In that sense, forgiveness is a decision, a step of obedience and it is a lifelong exercise. Jesus said forgive 7 times x 70 times, that means endlessly. So, we shall not give up.

CT: After 25 years, what do you see as the greatest need facing communities that were affected by the genocide? In what way are people still living with it?

DU: Twenty-five years after the genocide, we are very thankful for the positive steps towards unity and reconciliation that have been taken by government. But still the greatest need facing the community that was affected by the genocide is the issue of trauma among survivors and the transgenerational trauma.

Young widows, elderly widows, young orphans need support in trauma counselling.

In the community of Iriba Shalom Rwanda in the south-west, women were forced by the Hutu militias to bring

their baby boys and their heads were cut off with machetes in front of their mothers. They threw the babies' heads into latrines. Others were forced to kill their own baby boys.

Many women were raped and infected by HIV/AIDs and they are suffering in their daily life because they are not able to work hard because they are weak. Many elderly widows do not have children so they need more care and support in their old age because they have no one else to look after them.

Those who were orphaned young are still dealing with the issue of trauma. They are looking for opportunities to find a job and need financial support to stay out of poverty.

CT: What is Iriba Shalom International doing to help write a new future for these communities?

DU: We work with two organisations in Rwanda - Iriba Shalom Rwanda in the South West and Shalom Ministries in Kigali and Ruhango. We provide individual and group trauma counselling using a community-based approach but also provide practical support, like building and repairing the houses of widows, helping people who lost limbs to receive prosthetic limbs, supporting widows who adopted children left orphaned by the genocide, and helping with micro credit and income generation. It is a work of healing the wounds, building up people's dignity and fostering reconciliation.

Denise Uwimana tells her story in full in her new book 'From Red Earth', out on 25 April 2019 from Plough Publishing.